- Home

- San Francisco Attractions

- Chinatown

- Chinatown History

San Francisco

Chinatown History

The story of America's oldest Chinatown.

For over 150 years, San Francisco has had a significant Chinese population, and until the 1940's, most of the San Francisco Chinese lived in Chinatown.

Children in SF Chinatown, around 1900. By Arnold Genthe

Children in SF Chinatown, around 1900. By Arnold GentheArnold Genthe was a photographer in San Francisco around the turn of the century who took many fascinating photos of Chinatown scenes. His photos are the only known images of the Chinatown area before the 1906 earthquake.

San Francisco Begins in Chinatown

The first private residence in San Francisco (then called Yerba Buena) was an adobe house, built around 1822 by an English sailor in Portsmouth Square, in the heart of what is now Chinatown.

In 1846, Captain John Montgomery sailed over from Sausalito with 70 soldiers and raised the American flag in Portsmouth Square, claiming San Francisco for the United States. The handful of houses built around the square was the beginning of San Francisco.

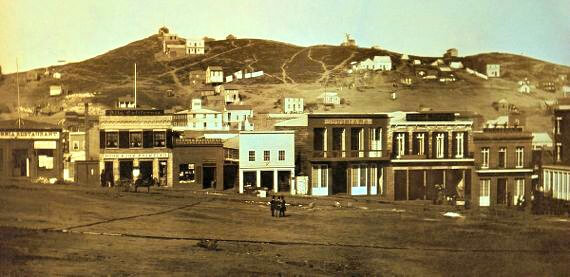

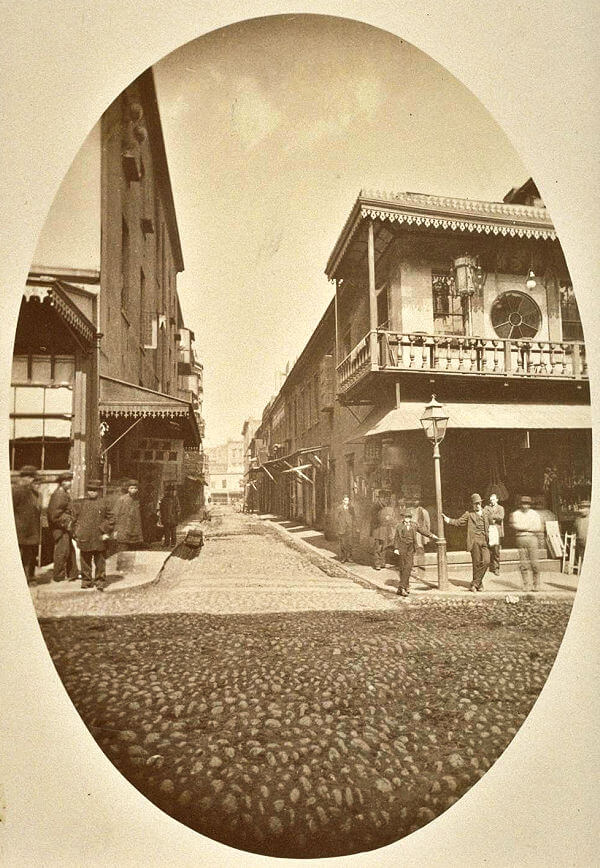

Portsmouth Square, 1851

Portsmouth Square, 1851Grant Avenue, currently the main street in Chinatown, was San Francisco's first street.

The Beginning of Chinatown

The first Chinese arrived in San Francisco in 1848: a man and two women. And only two years later, 20,000 Chinese arrived in "Gold Mountain".

Eureka! Gold in the Hills

In January of 1848, gold was discovered in the Sierra foothills, and The Gold Rush was on.

When word of the gold discovery reached China, many men left their homes and took ship for California. San Francisco was the port of entry, and the place where miners got provisions before heading inland to the gold fields. Chinese merchants began building shops in what is now Chinatown; this area used to be about a block from the bay and was essentially the first port of San Francisco.

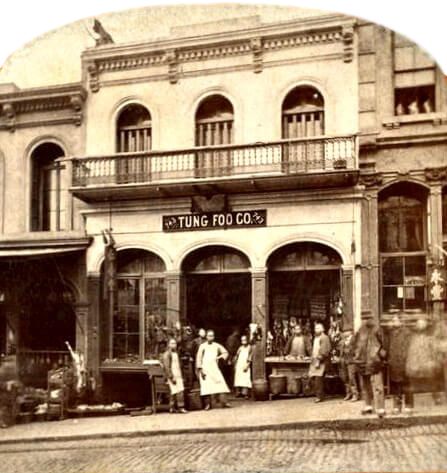

Chinese Store, San Francisco Chinatown

Chinese Store, San Francisco ChinatownChinese Immigration

The building of the Transcontinental Railroad in the mid 1800's also resulted in a large increase in the Chinese population of San Francisco.

Hundreds of Chinese men had been brought in to work on the building of the railroad, and when the line was completed in 1869, they moved on to other places in California and the West to look for jobs. Many of these men came to San Francisco.

Toy Vendor, by Arnold Genthe,

San Francisco Chinatown

Toy Vendor, by Arnold Genthe,

San Francisco ChinatownThe Chinese population in San Francisco increased rapidly during the last half of the 19th century.

The area still known as Chinatown became the neighborhood where the new arrivals settled, partly because of the ease of living in a Chinese community and also because at that time Chinese weren't welcome in other areas of the city.

Chinese Woman, San Francisco.

By Arnold Genthe

Chinese Woman, San Francisco.

By Arnold GentheThe SF Chinese population decreased somewhat after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882; the change in immigration laws in 1965 saw another surge in Chinese immigration into San Francisco and it continues today.

After the immigration laws were tightened, Chinese attempting to enter the U.S. via San Francisco were held on Angel Island while their applications were being processed. The building where they were held has been turned into an interesting museum and is worth a visit. See more on the Angel Island Immigration Station.

Approximately one third of SF residents are Asian, and most of those are Chinese. New arrivals still often settle in Chinatown, although the residential areas of the Richmond and Sunset Districts in the western half of the city have become majority Chinese areas over the past few decades.

Chinese Religious Buildings

Chinese immigrants built temples in Chinatown, both Taoist temples, focussing on honoring ancestors and praying to Chinese gods, and Buddhist temples.

The Tin How Temple (or Tien Hou) in Waverly Place is the oldest Chinese temple in the United States. It is dedicated to the goddess Mazu (based on a real woman who died in 987 A.D.), called Tin How, or Empress of Heaven. She is seen as the protector of seafarers, and as such, much honored by Chinese immigrants in San Francisco. The temple was created in 1852; the original building was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and rebuilt in 1911. It is still a place of worship and is open to the public.

There is a large Buddhist monastery on Sacramento and Grant, the Red Mountain Monastery.

Christian churches were also built early on here. The First Chinese Baptist Church, also in Waverly Place, was first built there in 1888, and rebuilt after the earthquake.

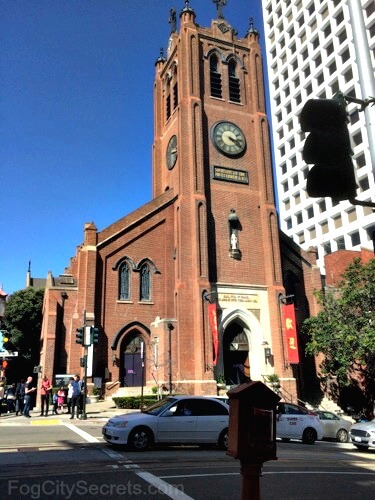

Old St. Mary's Cathedral at Grant and Pacific Avenues was built in 1854 from bricks shipped around the tip of South America, and was the only building in Chinatown to survive the fire that followed the 1906 earthquake.

Good Tongs and Bad Tongs

Chinatown became a city within a city; associations (tongs) were created by the residents and these organizations handled most of the affairs of the inhabitants: legal matters, criminal enforcement, banking, aid to newcomers, and more.

The Chinese Six Companies, were the main organizations which provided order and assistance to the San Francisco Chinese in Chinatown. They were based on family names or places of origin in China, and generally run by well-to-do merchants. They still exist today in the form of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association.

There were also a number of criminal organizations, basically gangs, also called tongs, that exercised power over the Chinese community through fear and intimidation.

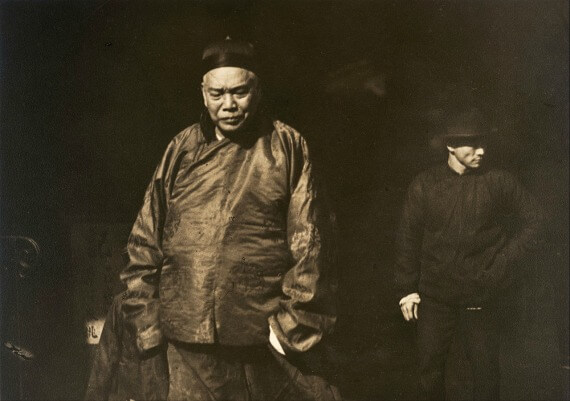

Chinese Merchant With Bodyguard.

San Francisco Chinatown, by Arnold Genthe

Chinese Merchant With Bodyguard.

San Francisco Chinatown, by Arnold GentheTong Wars

Like the gangs wars in New York and Chicago, Chinese gangs fought for dominance in the streets of Chinatown.

The Battle of Waverly Place. One of the most notorious gang fights occurred in 1879, when 50 men from two tongs fought in the small alley of Waverly Place over ownership rights to a Chinese slave girl, leaving four men dead.

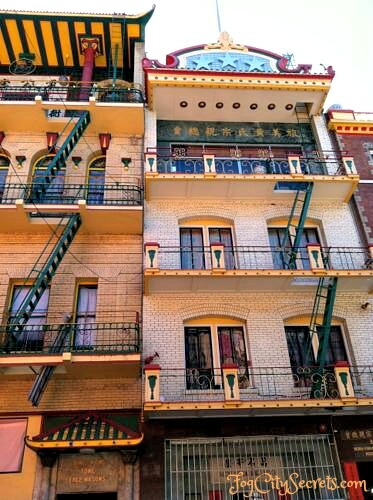

Waverly Place, aka the Street of the Painted Balconies, is now one of the prettiest and most charming alleys in Chinatown.

Waverly Place

Waverly PlaceCriminal gang violence still occasionally breaks out into the tourist world of San Francisco's Chinatown. Local gangs, and gangs associated with Hong Kong triads, have been responsible. Though Chinatown is generally a very safe place for tourists, there have been two alarming incidents in the modern era.

The Golden Dragon Massacre. In 1977, members of one Chinatown gang went to the popular Golden Dragon restaurant on Washington Street just off Grant Avenue (now the Imperial Palace restaurant). They planned to assassinate members of the Wah Ching gang who were eating there. They started shooting randomly, missed the gang members and ended up killing 5 other diners, including two tourists. The teenagers involved were caught and received long prison sentences; one them is still in prison.

Stockton Street Shooting. In 1995, members of the Jackson Street Boys, successor to an earlier local triad, started shooting at each other during daytime on the busy commercial street in Chinatown. Seven bystanders were hit, though fortunately no one was killed.

The Darker Side of Chinatown

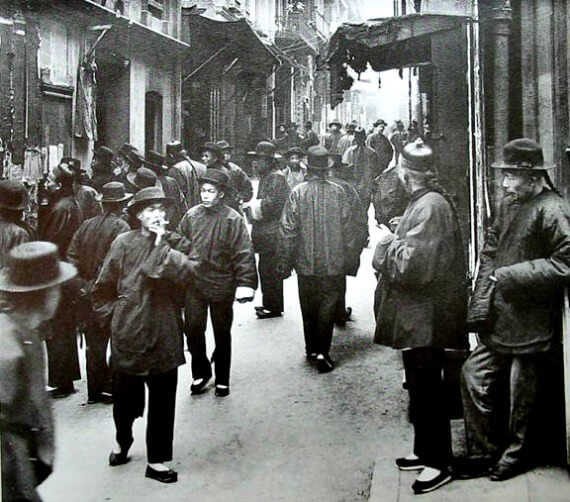

Chinatown in the 1850's until 1900 and beyond was a rough place, with thousands of poor immigrants from southern China packed into miserable, unsanitary tenements.

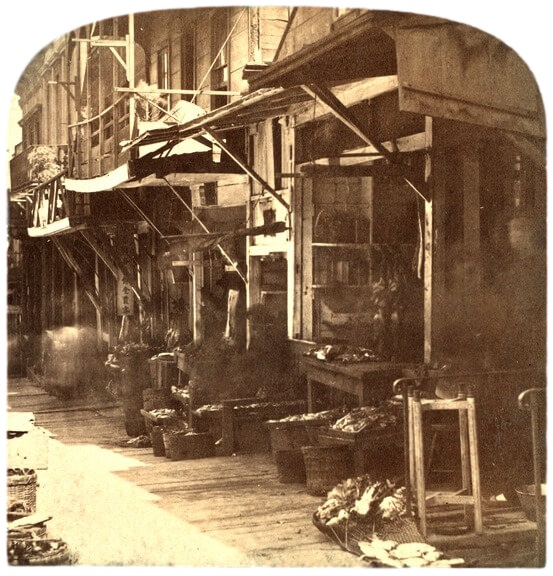

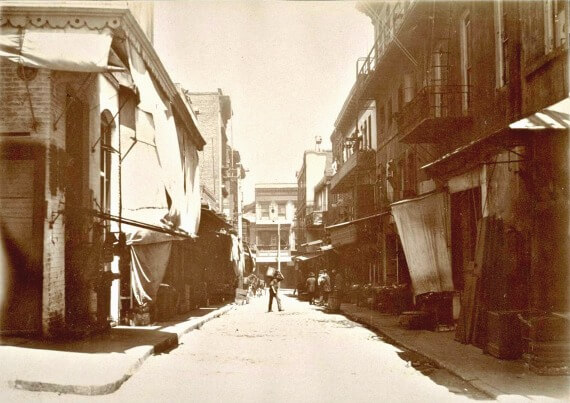

Chinese Shops, Sacramento Street,

San Francisco Chinatown, late 1800's

Chinese Shops, Sacramento Street,

San Francisco Chinatown, late 1800'sChinatown Alleys

It was in the alleys of Chinatown where most of the vice occurred. Some were lined with gambling parlors, some with opium dens and most of them with brothels.

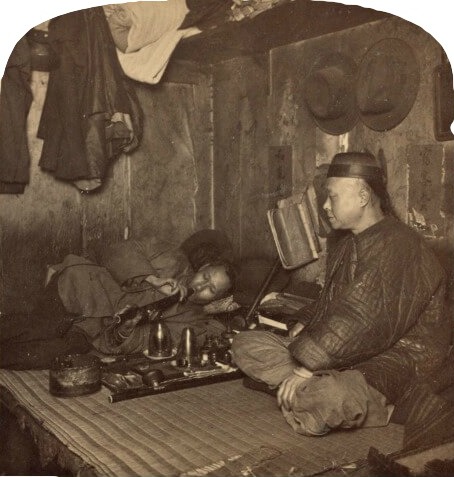

Duncombe Alley was known for its numerous opium dens.

Opium Den, Chinatown

San Francisco, 1898

Opium Den, Chinatown

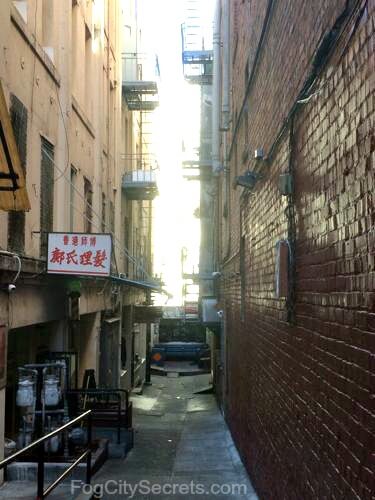

San Francisco, 1898 Duncombe Alley Now

Duncombe Alley NowRoss Alley was known as the Street of the Gamblers. These establishments had reinforced doors, often a series of them, to slow down the police, giving them time to hide the evidence. Also, there were tunnels under Chinatown connecting the buildings which were used to foil police raids (the tunnels vanished with the buildings in the great fire in 1906).

Ross Alley was also frequently the scene of tong warfare, and had its share of opium dens as well.

Ross Alley, 1898

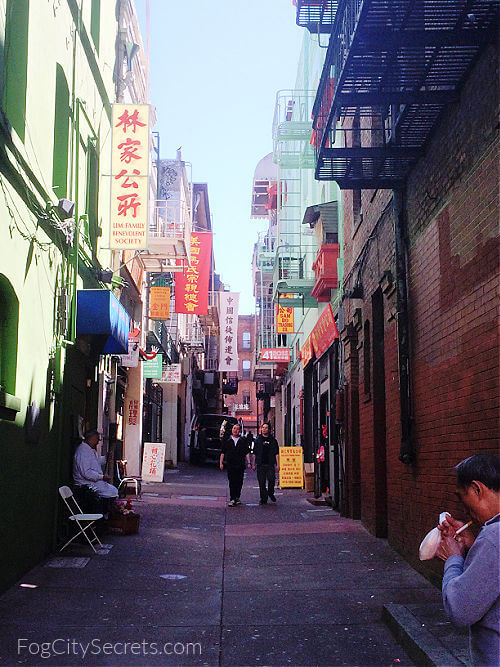

Ross Alley, 1898Ross Alley is now the location of the Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory.

Ross Alley Now

Ross Alley Now Washington Place, aka Fish Alley, late 1800's

Washington Place, aka Fish Alley, late 1800'sThe photo above shows Washington Place, looking towards Jackson Street.

Washington Place became Wentworth Place after the 1906 earthquake.

Wentworth Place

Wentworth PlaceSee article by Douglas Chan on the history of Washington Place, with historical images.

Prostitution

Because of the Gold Rush, most of the immigrants during this period were men, and this contributed to the demand for prostitutes; in 1850, only 8% of the San Francisco residents were female.

The criminal tongs imported young girls from China and sold them to brothel owners in slave auctions held in St. Louis Alley; most of these girls were between 10 and 16 years old, and they had a life expectancy of about five years.

St. Louis Alley Now

St. Louis Alley NowThe selling of slave girls was very profitable for the tongs; the average price for a girl at the slave auctions was $850, going as high as $2,000, but they were purchased in China for $90 to $300. The girls were acquired through various means. Some were sold by their own families, some were lured with promises of work, and some were kidnapped.

Much of the prostitution in Chinatown occurred in the alleys. Almost every building in Bartlett Alley was a brothel; some of the worst ones were on that passageway.

Bartlett Alley, now Beckett Alley

Bartlett Alley, now Beckett AlleySee article on the history of Bartlett Alley by Douglas Chan.

Bartlett Alley became Beckett Alley in 1908.

Beckett Alley Today

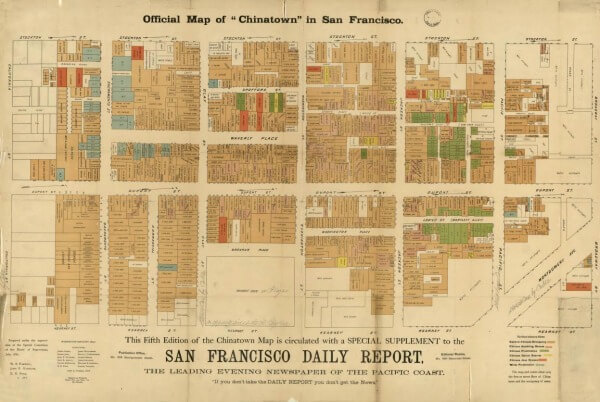

Beckett Alley TodayA map of the old Chinatown survived, showing the street and alley layout in 1885, as well as the location of the buildings associated with vice.

The key is hard to read:

Brown: General Chinese Occupancy

Pink: Chinese Gambling Houses

Green: Chinese Prostitution

Yellow: Chinese Opium Resorts

Red: Chinese Joss Houses

Blue: White Prostitution

Donaldina to the Rescue

The power of the tongs and the indifference of the other residents of the city left no one to fight for the protection of the young girls sold into slavery.

The Chinese Benevolent Association tried to curtail prostitution but didn't make much headway.

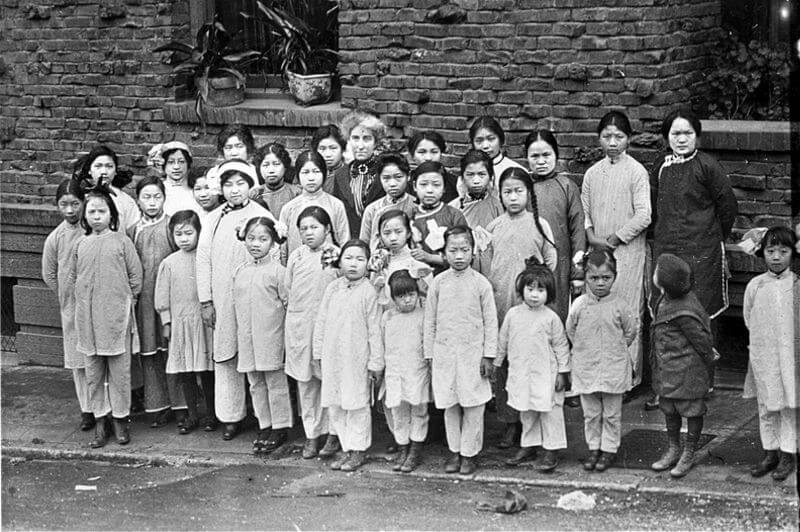

Donaldina Cameron took on the task of helping these girls escape and ran a Presbyterian mission in Chinatown to care for the rescued girls.

She also led raids on brothels herself and was called Fahn Quai, or White Devil, by her adversaries.

She lived to be 98 in spite of death threats from the tongs (and dynamite being left at her front door!).

Donaldina Cameron and Chinese girls at Cameron House

Donaldina Cameron and Chinese girls at Cameron HouseA very interesting article on KQED about a Chinese slave girl who rescued thousands of other girls in Chinatown.

A Tale of Two Madams

Most of the brothel owners were men, but two women achieved notoriety as madams of Chinatown brothels. One of them is buried in the cemetery at the Mission Dolores.

Ah Toy

A Chinese woman named Ah Toy was brought to San Francisco as a slave in 1849 to work in a brothel; she was reported to be tall and beautiful, and she became famous. In her mid 30's, she was able to buy her freedom and set up her own brothel in a Chinatown alley, Waverly Place

She was involved in the slave trade herself, purchasing young girls at the slave auctions held in a basement on St. Louis Alley.

She retired in 1859, supposedly married a wealthy Chinese merchant in San Jose, and lived to be 99.

Belle Cora

San Francisco's own Belle Watling, Belle Cora was the leading madam of Gold Rush San Francisco.

She arrived in San Francisco with her riverboat gambler husband, Charles Cora. They had made a fair amount of money in the mining camps, and used that to start a brothel in Chinatown, also in Waverly Place.

Belle Cora's brothel catered to San Francisco's "high society" of the time; luxurious, with lots of red velvet and higher priced ladies.

Her husband met with a sorry end. He shot a U.S. Marshall, Richardson, following a tiff at the theater when Mrs. Richardson objected to the presence of Belle Cora. Charged with murder, his trial ended with a hung jury, but Mr. Cora was hanged in 1856 in Portsmouth Square in Chinatown by vigilantes fed up with the rampant crime in San Francisco.

The word "vigilante" first came into being in San Francisco in 1851, as a result of the formation of the Committee of Vigilance dedicated to suppressing the extreme lawlessness and violence that was occurring in the streets of the city during the Gold Rush.

Charles Cora had company on the gallows. A city supervisor, James Casey, who had assassinated a newspaper editor for exposing his corruption, was hanged next to Cora.

Belle and Charles Cora are buried in the old cemetery next to San Francisco's Mission Dolores.

Hidden Office of Sun Yat-Sen

Dr. Sun Yat-Sen, the first President of the short-lived Republic of China, lead the movement that overthrew the Qing Dynasty in 1911. At one point during his exile, he lived secretly at 36 Spofford Street, raising support for the revolution.

Spofford Street

(#36 is just past the yellow building.)

Spofford Street

(#36 is just past the yellow building.)There's an attractive, burnished-steel statue of Dr. Sun Yat-Sen in St. Mary's Square in Chinatown.

The Chinatown Gate displays a quote of his (written in Chinese): "All under heaven is for the good of the people".

Sun Yat-Sen in St. Mary's Square

Sun Yat-Sen in St. Mary's SquareEarthquake

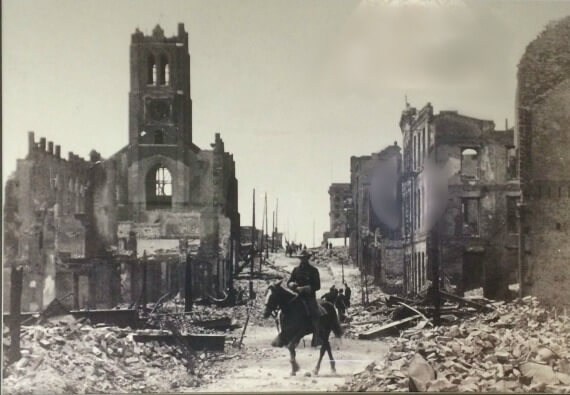

The 1906 earthquake in San Francisco set off a fire that consumed most of the older part of the city, including all of Chinatown. St. Mary's Church was the only surviving structure.

Chinatown scene after the 1906 earthquake.

Old St. Mary's Cathedral on left

Chinatown scene after the 1906 earthquake.

Old St. Mary's Cathedral on leftThe church has been fully restored, along with some beautiful stained-glass windows.

Old St. Mary's Cathedral

Old St. Mary's CathedralIt's generally believed that the church inscription under the clock, "Son Observe the Time and Fly From Evil", was aimed at the men who might be considering a visit to one of the brothels in the area!

There were plans to move Chinatown to another area of the city, but residents quickly rebuilt in the same location to head off those plans. The new Chinatown was built in the Edwardian style of the time, but with Chinese-inspired decorations added to the buildings. The buildings were intentionally designed to make the area appealing to tourists, and they did successfully create a suggestion of old China (at least to Western eyes).

Two of the first buildings to go up after the earthquake were the Sing Chong and Sing Fat buildings, sitting across from each other on the corner of Grant and California.

Sing Fat Building on Grant Avenue

Sing Fat Building on Grant AvenueThe "New" Chinatown

The destroyed wooden buildings were rapidly rebuilt with bricks, using the same street and alley layout. The brothels were also quickly rebuilt and back in operation, but their heyday was about to end.

San Francisco in the early 1900's was still a wild and lawless place, but the residents were getting fed up with the crime and corruption.

In 1907, the city's mayor, Eugene Schmitz, and the notoriously corrupt political boss, Abe Ruef, were convicted of bribery and sentenced to prison. They were known to take payoffs from Chinatown criminal enterprises, including gambling and prostitution.

Abe Ruef

Abe Ruef Eugene Schmitz

Eugene SchmitzIn 1913, the California legislature passed the Red Light Abatement Act to shut down brothels all over the state. This did effectively put most of the brothels out of business, though the San Francisco brothels were some of the last to go.

Commercial Street in 1907, between Grant and Kearny, was almost wall to wall houses of prostitution. The buildings at 742 (the "Parisian Mansion") and 736 were two of the last to close.

The Parisian Mansion

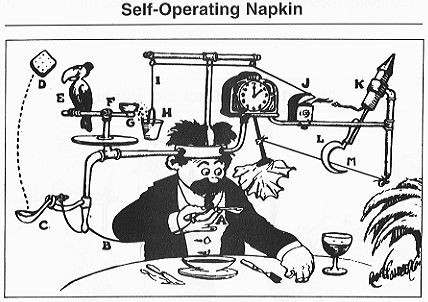

The Parisian MansionRube Goldberg, creator of the elaborate gadget cartoons, owned the house at 751 Commercial Street from 1906 to 1916; this house was also a brothel during those years, and Mr. Goldberg received the rents while living in New York City.

Rube Goldberg Cartoon, 1915

Rube Goldberg Cartoon, 1915 Rube Goldberg's House

Rube Goldberg's HouseMore Chinatown pages:

- What to see and do in Chinatown.

- Chinatown shopping: tips on the best places to shop.

- Chinatown restaurants: where to eat in Chinatown, and best dim sum places.

- Chinatown tours: recommendations for guided walking tours and do-it-yourself itineraries.

- Chinese New Year in San Francisco: parade tips and things to do.

More to explore...

Share this page: